Top 30 Cartoon Characters That Were Villains

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

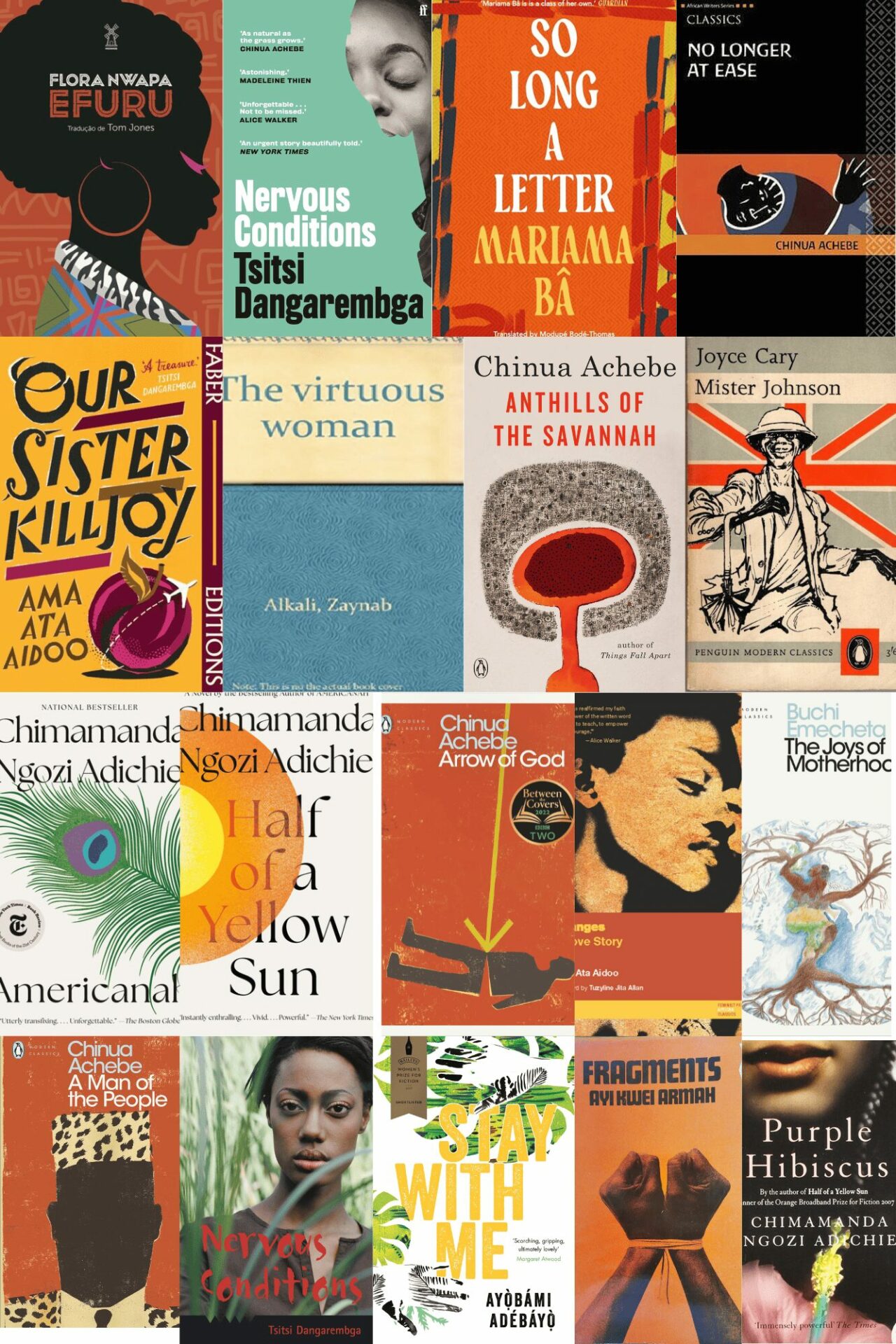

African Literature, Lists

Some African literary characters deserve applause. These ones? They come with virtually all the negative personality traits.

These characters weren’t just flawed—they were walking, talking red flags.

Some African literary characters deserve a big round of applause. These ones? A loud sigh and a side-eye.

They’re literally the toxic football club, with a baggage of virtually all the negative personality traits you can think of.

Check out our twenty African literature characters with negative traits, counting down from the mildly annoying to the downright monstrous.

The Mildly Annoying

Efuru is elegant, strong-willed, and unfortunately, terribly trusting. Her belief in love and second chances often blinds her to harsh realities.

Her optimism crosses into denial, and her repeated mistakes come from refusing to accept when something’s broken beyond repair. Efuru means well, but sometimes, meaning well just isn’t enough.

Tambu escapes poverty through education, but she doesn’t just leave her old life behind; she starts looking down on it. As she grows, her narration becomes tinted with elitism.

She compares, judges, and sometimes forgets her own mother’s suffering. Her intelligence becomes a wall, separating her from those she should uplift.

Aissatou walks out on a cheating husband, which is iconic. But in doing so, she also walks away from vulnerability.

She becomes hard, guarded, and emotionally distant. Her strength is real, but it comes with a chill. Sometimes her pride keeps her from offering comfort when it’s needed most.

Obi returns from England full of ideals. He hates bribery… until he needs money. He wants to marry for love… until it costs him social acceptance.

He talks about integrity, then folds under pressure. His downfall is sad, and it’s frustrating, because deep down, he knew better.

Sissie is sharp, reflective, and powerful. But her thoughts drip with judgment. She criticises Europeans, fellow Africans, and even herself, but never in a way that builds.

She isolates herself with her own intelligence, seeing people more as case studies than companions. It’s a lonely kind of brilliance.

Beatrice is intelligent and aware, but far too often, she stays quiet. In the face of political decay and personal loss, she watches from the sidelines. Her silence becomes complicity.

Her intellect never translates into action, and by the time she finally speaks, the damage is done.

Mr. Johnson wants to be English so badly, he forgets how to be himself. He romanticises colonialism and clings to white approval like oxygen.

His cheerful nature hides deep confusion and self-hatred. He doesn’t realise he’s the joke until it’s too late.

Aunty Uju is smart and ambitious, but she sacrifices her integrity for financial comfort. She stays in a toxic relationship for security and raises her son in half-truths.

Her choices are understandable, but her willingness to justify them is troubling. She teaches survival, but not truth.

Ezeulu believes he alone understands the gods. His pride swells until it eclipses reason. He refuses compromise, punishes his own people, and watches a village collapse because he won’t budge.

His spiritual leadership becomes tyranny wrapped in rituals.

Kainene is sharp-tongued, independent, and impossible to read. She hides pain behind sarcasm and holds love at arm’s length.

Even in war, she wears armour made of attitude. Vulnerability terrifies her, and she makes those who love her feel like intruders.

Nana wants a modern love story but expects it to follow old rules. She criticises patriarchy, then willingly enters a polygamous marriage.

She calls herself liberated, but her actions scream confusion. She mixes feminism with fantasy and ends up in emotional quicksand.

Nnu Ego’s world revolves around children. But she weaponises sacrifice and becomes blind to the damage she causes.

She guilts her children, judges other women, and refuses to see beyond tradition. Her devotion strangles everyone, including herself.

Chief Nanga is the poster child for “smiling evil.” He bribes, cheats, and charms his way through politics. He uses tradition to excuse tyranny and makes oppression look like culture. He doesn’t just bend morals, he snaps them like twigs.

Downright Monstrous

Nyasha’s rebellion turns inward. She burns with intelligence and fights injustice, but she also lashes out at everyone who tries to love her.

Her rage becomes uncontrollable, and her pride isolates her.

Okonkwo fears weakness more than death. His obsession with strength makes him cruel. He beats, shames, and controls, all to protect his fragile image.

When the world changes, he refuses to change with it, his pride becoming deadly poison.

In the book Stay With Me, Akin calls it love, but it’s control. He makes decisions for his wife without her, hides truths, and breaks vows. He plays the victim even when he’s the problem. Soft voice, sharp knife.

Baako sees himself as too pure for a dirty world. He judges from a pedestal, talks in riddles, and pushes people away. His failure to connect turns his ideals into insults. He becomes a ghost among the living.

Ifeoma wears independence like perfume. She says the right things, but rarely feels them. She sees suffering, but responds with theory. Her distance makes her safe, but it leaves others cold.

She’s warmth with a wall.

Papa Eugene is respected, righteous, and terrifying. He punishes in the name of God, controls his family with fear, and masks abuse with scripture.

His public charity hides a terrible, private cruelty.

The Tyrant Overlord. Fantasy buff and avid football fan.

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

DC is great at making comics and animated movies, while the MCU has the upper hand in its cinematic aspects

Discover the best apps to read books for free in 2025. Access thousands of free e-books and audiobooks on your phone or tablet. ...

There are some outright funny cartoon characters who exist solely to crack you up, loud, hard, and with zero apology.

Things Fall Apart is for the colonizers as well as the colonized, helping to understand the role of colonialism in the realization...

While many of the Nollywood movies on our list are quite old, it’s a testament to the capabilities of the industry’s p...

While this isn’t an exhaustive list, it comprises some of the most popular mythical creatures from around the world.