“Stories are critical… The minute we fall silent, someone will fill the silence for us.”

One word for how I felt after reading this book is content. I felt full.

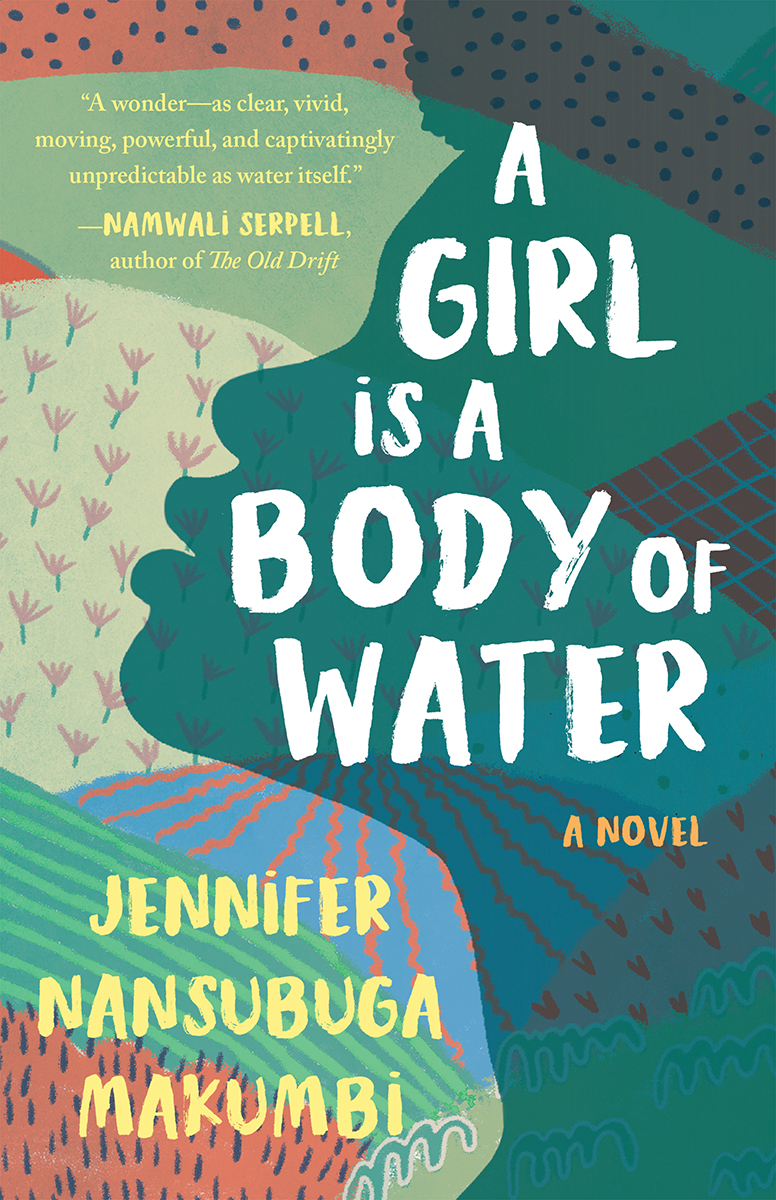

The book is a story about life as a woman and the societal expectations that comes with it. It is straightforward, honest, witty, and open. This book is a 5-star must-read for everyone, as the author minced no words in her storytelling.

The protagonists in this story are a generation of women fighting to be seen. There is Kirabo, the granddaughter of Miiro and forgotten child of Tom, Nsuuta, who took life by the horns and lived it on her own terms regardless of the name-calling, and Auntie Abi, daughter of Miiro and Alikisa (Muka Miiro) who was determined to change existing narratives and raise Kirabo as a self-aware woman.

The dominant theme in this book is mwenkanonkano (feminism).

The book is set in the 1980s, a significant period for people in Uganda and women globally. In the West, women demanded change, insisted on their rights, and fought discrimination during the second wave of feminism.

In the beginning, in Natetta, women were groomed to marry men. You had to marry as a virgin, and your aunt got a goat glorifying your virginity. Women took care of homes, stayed with their husbands, raised their babies, and were homemakers. Women did not inherit lands or anything from their fathers or husbands. They served a utility and got nothing in return.

Then came Lutu, Miiro’s father, who took his children to school and gave his daughter land even though women were not allowed to inherit land according to Natetta culture. Women were allowed as far in life as the men in their lives will let them.

As Lutu and his son Miiro made significant adjustments in how they adhered to culture, significant changes were happening worldwide. The second wave of feminism which was around the 1960s-1980s, was about women’s reproductive rights- women fighting for body agency, wanting control of their bodies. Basically, second-wave feminism focused on equality and discrimination. And, it’s no wonder that Kirabo, Nsuuta, Auntie Abi, and other women were also fighting vehemently to end discrimination against daughters in the family.

Auntie Abi wanted Kirabo to be named Tom’s successor instead of her youngest sibling, junior Tom, since she was the firstborn and indeed would be the one taking care of her siblings. This was unheard of and was faced with a lot of criticism. So, she fought for Kirabo to own Tom’s house and lands. Even though Kirabo was not named the successor, there were victories; women began to recognize their rights and demand them, leading to women starting to inherit lands.

Although Miiro’s family allowed women to inherit lands, they could not pass it on to their own kids. They had to pass it to their brothers’ kids because their own kids were regarded as belonging to their partners’ clans. The danger with this was that women were reluctant to develop lands they inherited from their fathers because they could not pass it on to their own kids.

So even though boundaries were broken, it wasn’t a big victory but a victory nonetheless.

Girls were not supposed to be assertive. They were not supposed to want men or pay attention to male affection. Instead, they were supposed to perform outrage. When a boy expressed interest in you, you were supposed to perform outrage. But times started changing in the 80s for women in Natetta and women globally.

People would have you believe that feminism is a concept that was birthed in the 90s and 2000s, but this book is evidence that feminism has always existed before the 60s

I enjoyed this book way more than I thought, and I laughed a lot because Kirabo was very hilarious.

Another dominant theme was family and communalism. People in Natetta lived together like a family. They helped each other and were there for each other.

One thing is for sure- a child belongs to the whole village, and I am a living testimony of it. It doesn’t matter who births you but who was there to raise you.

When Alikisa gave birth to Tom, she gave her to Nsuuta to take care of him as hers. After all, she had promised to give birth for Nsuuta.

When Kirabo was born, Tom took her home to his parents (Alikisa and Miiro), and his sisters raised her as theirs. Auntie Abi said when Kirabo arrived, she knew that Kirabo was hers. The whole village looked out for her, advised her, was there for her. When she moved to the city to live with Tom, communalism and a sense of family was one thing she missed about Natetta.

Tom’s passing revealed how feeble human life was. Kirabo said packing all of Tom’s things in the car made her see how lofty Tom’s dreams were. The women in Tom’s life treated him like a god, so they realized how unrealistic that was when he died. How Makumbi announced Tom’s death tells you how tragic his death was and the gap he left behind.

“Tom died. He died without reason, without warning, without goodbyes—right in the middle of life.”

He died right in the middle of life when life was going on and when everything was good and robust. Tom died

One thing I absolutely love about this book is how Makumbi writes unapologetically in Luganda. She doesn’t bother explaining what Muka means or writes Mrs. Miiro or wife of Miiro; she just writes. She writes Kitalo and all the Luganda words, which got me running to social media looking for someone who speaks Luganda, and I’m dying to hear how they are pronounced. I feel like if this book is made into an audiobook, it will give me the vibes Nervous Conditions gave me, and I would be excited.

…few fingers of matooke off a bunch leaning against the wall, and started to peel. “I will boil these in tomatoes and onion leaves, maybe drop doodo on top?” Nsuuta nodded. “Maybe a dollop of ghee?”

I love how she wrote in Luganda unapologetically especially writing the food the way she understands

Another take home is how we should not reduce femininity to the vagina. Kirabo showing her vagina to Sio was a way of her banishing the shame. Don’t put a target on women’s bodies, don’t make it a mystery. If not, people would want to know what the fuss is about. This was Kirabo’s theory, and I totally agree. It is disconcerting to limit feminine power to the vagina. It reduces girls to nothing but their sexual organs.

“Nsuuta, it is dangerous keeping feminine power down there. Whether it is in myths or in mystery, we put a target on our bodies. Sooner or later, they come to raid. Unless you did not hear about the women raped during the war.”

At first, you would think Sio and Kirabo’s relationship would shatter glass ceilings, but here we are. Sio impregnates Giibwa and expects Kirabo to forgive him and resume their life. He expects his daughter to come and live with them, and Kirabo must accept it.

Although Giibwa betrayed Kirabo, Kirabo could not help but cringe at what Sio said for someone who claims he is progressive. He didn’t even ask Kirabo what she wanted, whether she even wanted to mother someone’s daughter, and even though Sio never had sex with her, he thought Giibwa was disposable to have sex with. To be used, even if it was just once.

The dynamics between Sio and Kirabo reflects the mind of men, especially men who claim to understand feminism.

I love Auntie Abi; she was so blunt. She takes care of Kirabo and mothers her as a progressive parent will.

Nnakku, the woman who gave birth to Kirabo… She was 13 years old!! You could say that she was heartless in the way she denied Kirabo, but I think she didn’t have a choice at that age. What would you have done better?

It’s an experience you would erase from your mind, even if it includes a full human being coming back into her life. It was probably a reminder of her youthful mistakes, which she wasn’t ready for. Accepting Kirabo meant that she accepted it happened. No matter how heartless it looked, I don’t blame her for rejecting Kirabo.

I also learned about labia elongation. Apparently, labia elongation facilitates orgasm and female ejaculation and is considered to enhance sexual pleasure for both partners.

One thing I like about this book is how Makumbi places a lot of importance and wealth on work like Farming. Sio, with all his education, dreams of being a farmer. Similarly, Miiro, from a wealthy family who studied in the city, wanted to be a farmer and returned to be a wealthy farmer with lands.

The language is impeccable, and I totally recommend this book without any reservations and with all the gods in my village backing me.

Feel free to check out this review of Kintu, by the same author.