Top 30 Cartoon Characters That Were Villains

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

Essays

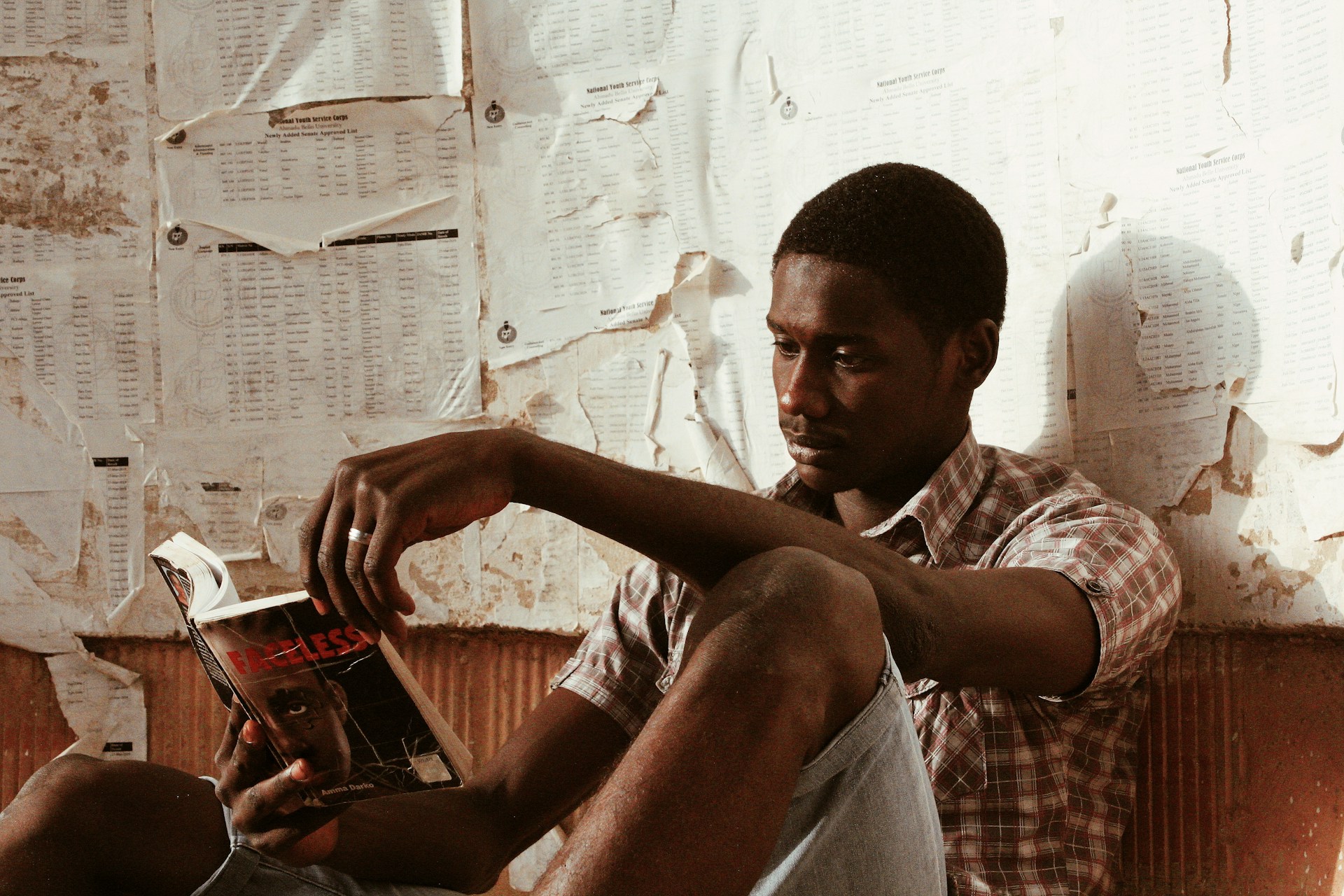

Fiction doesn’t promise solutions. It doesn’t moralize. It simply offers a window into someone else’s world and asks: Can you stay here a while?

We spend our days brushing shoulders with people whose lives we’ll never understand. But fiction, unlike life, stops us long enough to feel what it’s like to be someone else. And sometimes, that’s the only way we ever do.

Empathy isn’t always innate. Contrary to the popular belief that it comes naturally, it’s often something we learn; awkwardly, slowly, and sometimes too late. Life gives us plenty of opportunities to practice, but it rarely hands us the time or space to imagine another person’s interior world fully. Fiction, though, makes this its sacred task.

I’ve cried over characters who don’t exist, grieved relationships that were never mine, and found myself changed, softened, by the emotional truths of people born only from words. That’s the strange alchemy of fiction: it conjures lives that aren’t real but teaches us something profoundly true about the lives that are.

In real life, people’s pain is often muffled by politeness, distraction, or our own discomfort. We walk past someone sobbing on a bench, scroll past a tragic story, nod sympathetically at a friend’s heartbreak, but still check our phones when they pause to breathe.

Fiction is different. It demands our stillness. It gives us uninterrupted access to the messy, conflicted, and intimate truths of other people’s minds. In fiction, there are no social masks; just unfiltered grief, shame, doubt, desire, and fear. We don’t just observe suffering; we inhabit it.

We become the young girl in Kabul who hides books under her burqa. We are the aging professor who forgets his daughter’s name. We feel the hunger of a boy in wartime, the rage of a woman silenced by centuries.

And in doing so, something shifts in us. Not abstract sympathy, but genuine connection.

Empathy isn’t just about feeling sorry for others; it’s about understanding. And understanding is often where life fails us. Reality, for all its intensity, is also chaotic and messy. We encounter people mid-story, without context or conclusion. A friend’s anger might seem unjustified until we learn the whole history. A stranger’s cruelty might be fear. But we don’t always get to know.

Fiction gives us the luxury of full context. We start at the beginning and, most of the time, stay until the end. We’re given backstory, motivation, and nuance. We’re allowed to sit with contradictions: characters who are both selfish and generous, loving and destructive.

And in recognizing these contradictions in fictional people, we start to recognize them in real people, too.

Studies show that readers of literary fiction perform better on tests of emotional intelligence and theory of mind. In other words, they’re better at guessing what others are feeling or thinking. That’s not an accident. Fiction trains us for this exact thing. It enlarges our moral imaginations.

When we read books like Born on a Tuesday, Second Class Citizen, A Little Life, or The God of Small Things, we don’t just consume stories. We expand our emotional bandwidth. We get better at sitting with complexity, at resisting judgment, at responding with care.

And what a world it could be, if more of us learned to do that.

Fiction doesn’t promise solutions. It doesn’t moralize. It simply offers a window into someone else’s world and asks: Can you stay here a while? Can you care, even though it’s not your life?

That invitation is powerful. And when we accept it, we come away not just better readers—but better humans.

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

DC is great at making comics and animated movies, while the MCU has the upper hand in its cinematic aspects

Discover the best apps to read books for free in 2025. Access thousands of free e-books and audiobooks on your phone or tablet. ...

There are some outright funny cartoon characters who exist solely to crack you up, loud, hard, and with zero apology.

Things Fall Apart is for the colonizers as well as the colonized, helping to understand the role of colonialism in the realization...

While many of the Nollywood movies on our list are quite old, it’s a testament to the capabilities of the industry’s p...

While this isn’t an exhaustive list, it comprises some of the most popular mythical creatures from around the world.