Top 30 Cartoon Characters That Were Villains

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

Essays, history

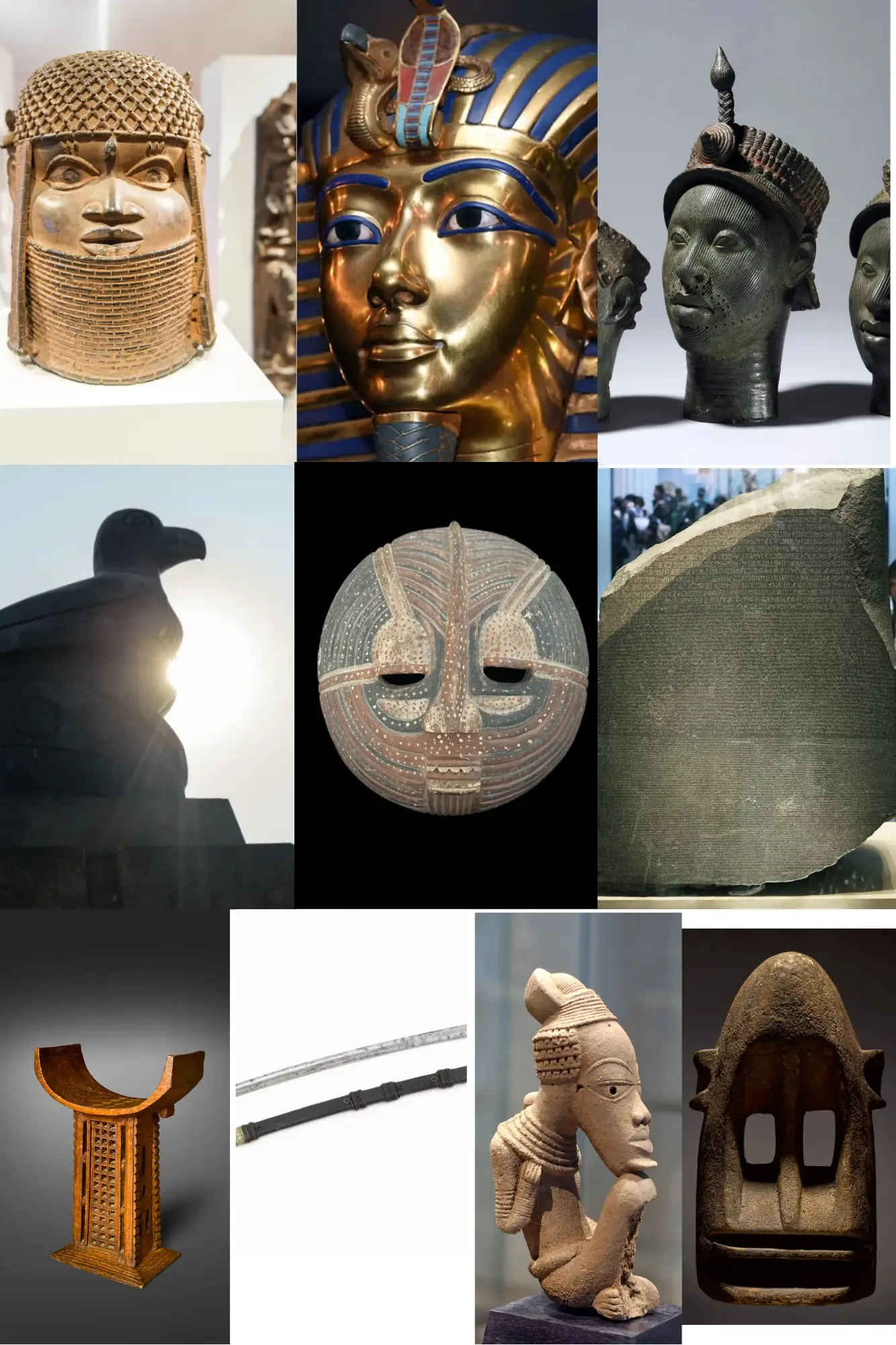

Here are 10 African artifacts showing how Africa’s artistry has never been associated with the negative connotations projected.

False stories with racial undertones have plundered Africa’s history. Colonials labelled Africans “primitive” while stealing and showcasing our artifacts in European museums. Songs, traditions, stories, and dust now carry the fragmented memories of lost civilizations.

Today, these African artifacts tell stories that colonizers once silenced, rewrote, and misconstrued. People are now remembering, studying, and returning them to their origins.

Here are ten African artifacts that celebrate creativity, culture, and resilience. They show Africa’s artistry has never deserved negative connotations.

In the heart of Benin City, the ancient capital of the Edo Kingdom, the royal court displayed brass plaques and sculpted figures. These were the Benin Bronzes. They were elegant pieces of metalwork that defined royal life, ceremonies, and highlighted power.

When British troops invaded in 1897, they burned the city and looted thousands of pieces. Collectors shipped the artifacts to London, and many are still on display in major European museums.

For the Edo people, the bronzes were sacred records that linked the Oba or King to his ancestors. Each plaque carried history in hierarchies.

Recent shipments from Europe have returned these artifacts, symbolically reawakening a royal legacy long trapped behind foreign glass. Moving north from Benin, Egypt also boasts artifacts revealing ancient connections between art and belief.

In 1922, deep in the Valley of the Kings, British archaeologist Howard Carter uncovered the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Archaeologists found the young King’s face sculpted in lapis lazuli, gold, and quartz.

Artists crafted the mask not for display, but for eternity. Ancient Egyptians believed it guided the pharaoh’s spirit to the afterlife.

The Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo preserves the mask, which remains there today. Its craftsmanship testifies to a civilization that saw art as a divine expression. Communities believed that faith and art were inseparable.

Archaeologists discovered the Ife heads in 1938 in Ife, a town in southwestern Nigeria, considered the Yoruba homeland. They amounted to eighteen heads, including one broken king figurehead.

These works were so naturalistic, with clearly defined human features, that early colonial scholars refused to believe Africans had created them. Sculptors in Ile-Ife, between the 12th and 15th centuries, crafted symmetrical faces that reveal a society of profound artistry.

These heads, some adorned with fine lines, designs, and elaborate hairstyles, signified divine kingship. Their calm expressions reflected sacred power. Colonial powers took many, placing them in museums abroad, while others thieves stole and sold.

Altogether, these African artifacts serve as enduring evidence that this great continent’s genius was always present.

In central Nigeria, archaeologists excavated terracotta figures beneath the red earth near Nok village. These artifacts date back to around 1000 BC.

With detailed hairstyles, expressive faces, and jewelry, they belong to one of Africa’s oldest known civilizations.

Nok artistry reveals intricacy. Some figures likely represented ancestors, leaders, or deities. Unfortunately, looters have stolen countless pieces, selling these objects into private collections worldwide. Others remain in Nigerian museums, offering tangible evidence of a complex civilization through African artifacts that thrived before foreign intervention.

In Bandiagara, Mali, the Dogon people live a life of ritual and reverence. Their masks, especially the Kanaga mask, with its double crosses, appear in funeral dances meant to guide the souls of the dead to the ancestral realm. Each mask represents something: a connection between heaven and earth and a balance between worlds.

When Europeans first encountered them in the 20th century, these masks were referred to as “tribal art.”

Many now reside in museums abroad, detached from their meaning. Still, for the Dogon, the mask remains a living sign of tradition.

Eight soapstone birds were discovered in the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, a city built by the Shona people between the 11th and 15th centuries.

Carved with both human and bird features, they once stood on tall stone pillars within the royal court, serving as spiritual symbols of the ancestors and guardians of the kingdom. Historians believe it symbolized the ancestors who were the guardians of the Shona people’s royal lineage.

When colonial settlers “discovered” Great Zimbabwe in the 19th century, they refused to believe that Africans had built it and took several of the birds to South Africa.

After independence in 1980, some of the birds were finally returned, although one remains abroad. Today, the Great Zimbabwe Bird stands proudly on Zimbabwe’s flag and currency, signifying a restored emblem of identity.

Found among the Luba and Songye peoples of Central Africa, the Kifwebe mask is characterised by bold, striped designs.

The colours red and white represent duality, embodying both order and chaos, as well as the concepts of male and female, and good and evil; the colour black stands for mystery. The lines on the masks represent spiritual maps, channelling energy during initiation and political rituals.

The masks’ exaggerated forms inspired countless modern artists in Europe. Yet, their meaning was rarely acknowledged.

During the colonial administration, these masks were taken and sold as curiosities, while they were, in fact, symbols of spiritual connection, justice, and protection.

In 1799, a French soldier discovered a granodiorite stele near the Nile Delta in a small town called Rosetta. The stone was found carrying inscriptions of a decree dating back to early 196 BC, issued during the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt.

These inscriptions were in Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphic scripts. The stone became the key to deciphering the language of the pharaohs.

After the British defeated Napoleon’s forces, they seized the stone and shipped it to London, where it remains in the British Museum despite Egypt’s repeated requests for its return.

The Rosetta Stone stands as a symbol of the seizure and colonization of intellectual heritage.

In the old Kingdom of Dahomey (present Benin), every King had a throne. They were carved from wood and marked with symbols that told stories of the King’s reign.

Following the French invasion of Abomey in 1892, not only land but also cultural treasures and the insignia of royalty were taken. The thrones of King Ghezo and King Glélé were taken to Paris, where they are currently housed in the Musée du Quai Branly.

King Adandozan’s throne followed a different path, having been sent as a gift to Portugal in the early 1800s before being moved to Brazil’s National Museum. Sadly, it was lost in the 2018 fire that destroyed a significant portion of the museum’s collection.

Only a few royal thrones remain, but each retains part of Dahomey’s history. Taken together, they demonstrate how African artifacts have endured over time.

Omar Saidou Tall, also known as El Hadj Omar Tall, led West Africa as a 19th-century scholar and founder of the Toucouleur Empire. His Islamic state once spanned parts of present-day Senegal, Mali, and Guinea.

He led resistance movements against French colonization in West Africa with his sword. The blade was French-made with a handle shaped like a bird’s beak. In April 1893, French troops reportedly seized the sword from his son, Ahmadou Tall, in Bandiagara, Mali, after Ahmadou’s military defeat in battle, making it a war prize captured by colonial forces.

For decades, France’s Musée de l’Armée in Paris housed the sword. It was later temporarily loaned to Senegal’s Musée de la Civilisation Noire in Dakar.

Then, in 2019, France formally handed it back to Senegal during a state ceremony. This marked one of the first major restitutions of African heritage under President Emmanuel Macron’s pledge to return looted artifacts from the colonial era. For Senegal, the return of the sword reclaims a pride and identity that once seemed out of reach.

The journey of Africa’s artifacts tells a diverse yet complicated story; one that goes beyond art and delves into politics, law, and raises questions about the morality of history.

Each piece, whether it rests in a foreign museum or its homeland, reveals how colonial power once controlled not just land and people, but memory itself.

Today, as countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and Senegal push for the return of their heritage pieces, the debate has shifted from symbolism to accountability. Museums now face scrutiny for how these objects were acquired, catalogued, and displayed. Laws such as Britain’s Museum Act of 1963 and France’s heritage regulations still make restitution difficult, but the tide is shifting.

It has become clear that restitution is not to be taken lightly. Returning these artifacts is not just a means to correct the past but a way to restore legacy, dignity, and the right to cultural preservation and representation. It demands that the continent reclaim the authority to tell its story on its own terms.

Timiebi Anthony is a content writer specializing in food journalism, culture, and storytelling. She creates research-driven content across lifestyle, SEO, and creative writing, with a focus on clarity and audience connection. Currently pursuing an English degree, Timiebi blends academic insight with practical expertise to deliver compelling narratives.

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

DC is great at making comics and animated movies, while the MCU has the upper hand in its cinematic aspects

Discover the best apps to read books for free in 2025. Access thousands of free e-books and audiobooks on your phone or tablet. ...

There are some outright funny cartoon characters who exist solely to crack you up, loud, hard, and with zero apology.

Things Fall Apart is for the colonizers as well as the colonized, helping to understand the role of colonialism in the realization...

While many of the Nollywood movies on our list are quite old, it’s a testament to the capabilities of the industry’s p...

While this isn’t an exhaustive list, it comprises some of the most popular mythical creatures from around the world.