Top 30 Cartoon Characters That Were Villains

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

Essays, Opinions

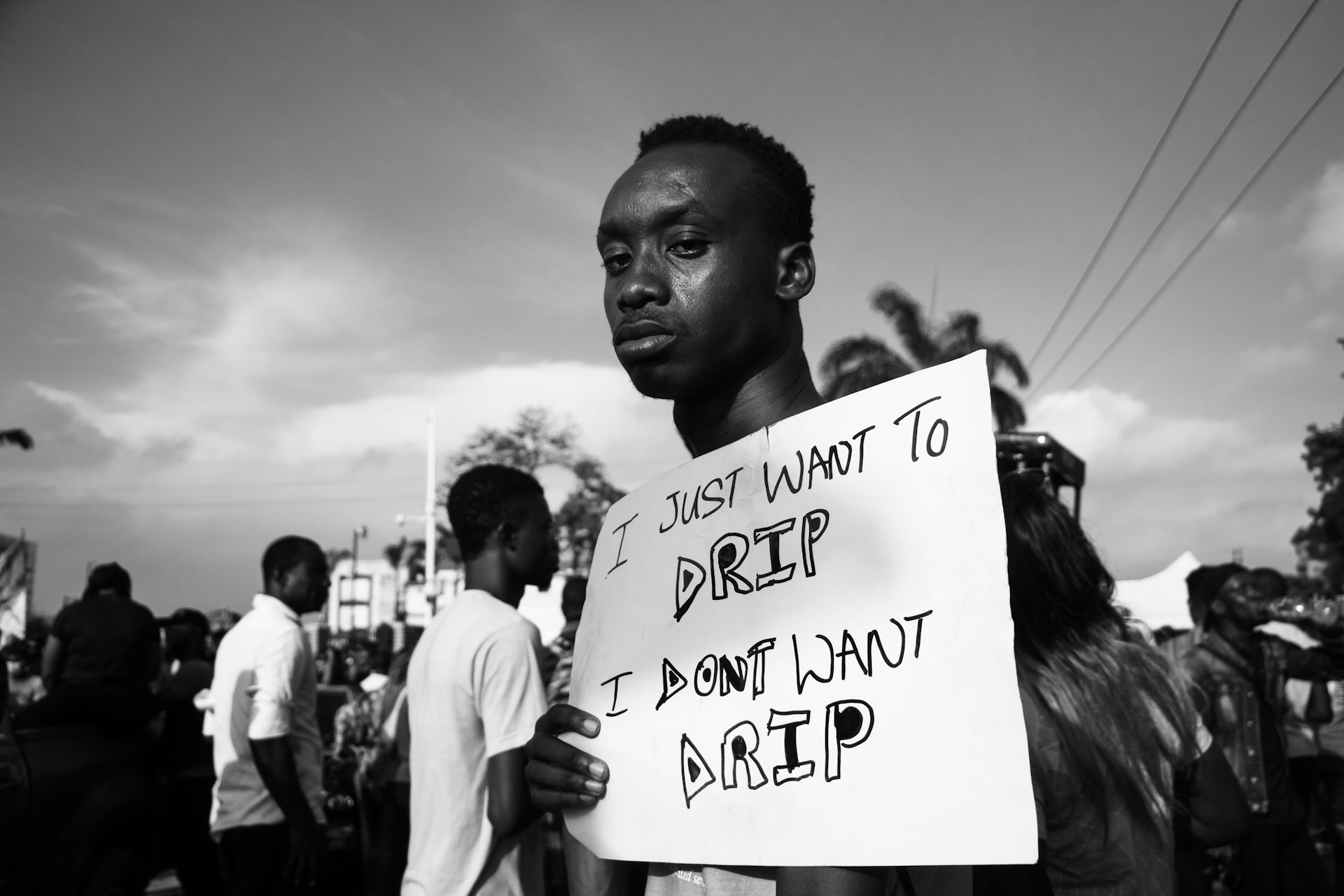

Until the image is completely shed, African Literature will be synonymous with Africa’s bleakest realities, with no glimpse at its hidden riches.

Trauma-porn.

The very words hint at a “glorification” of tragic themes in African Literature. They’re supposed to be a reminder of our grim past, bleak present, and even murkier future.

Supposedly.

After all, they’re only typifying the realities of life on the Black Continent – the physical and emotional abuse, the poverty, and the host of other sad themes that constitute the reality in this part of the world.

But is that really all there is to African Literature? Are the authors dwelling too much on trauma-porn? And, are there other unexplored themes different from this seeming proliferation of tragic stories?

If you ask the random bibliophile what comes to mind when the phrase “African Literature” is mentioned, you could wager your life that it’d be something along the lines of “suffering” or “sadness”.

For long, the stories of many African, and indeed Black authors around the world have reflected their reality. The realities of being trodden underfoot for no other reason than being dark-skinned; the ignominy of having to work twice as hard as others to get the same amount of recognition.

Black people around the world are all too familiar with these trials. We have, as one, been mentally beaten, stolen from, and harassed, with our very essence seemingly diminished. We’ve been on the wrong side of history’s biggest conflicts for so long that we continue to be colonized by the West long after our chains fell off.

It is no surprise that African Literature is filled with such sad stories.

This is a natural consequence of the development of poor nation-states and the continuous struggle to find a cultural identity whose core is slowly being chipped away with each new generation.

Personal experience is one of the biggest sources of creativity. So, who could blame the authors for writing what they’ve seen and lived? Who could blame them for writing so many books on patriarchal privilege, of how women continue to be abused, and the deep impact of poverty and social underprivilege?

These are the realities of African society.

But then, one realizes that African Literature is consumed not only in the Black continent, but by readers around the world. And, as much of a business as publishing is, authoring books remains inherently “storytelling”.

And, it is the stories that we tell that lay the groundwork for the African narrative as understood by Africans and non-Africans.

While there’s no harm in telling of our struggles, there is a real danger in rehashing the same themes.

We risk being perpetually seen by the rest of the world as exclusively what we have mostly portrayed – a group of savages whose only salvation lies in adopting Western culture and ideals.

There’s no bigger influencer of public opinion or image than the media. Indeed, there are many youths in the so-called third-world countries of the world whose mental image of the West includes towering skyscrapers, beautiful blondes at beaches, and stacks of greenbacks.

While the USA, along with its EU and NATO allies, is undoubtedly a world power today, one could argue that it has built a near-perfect image of itself in every regard, from infrastructure to society. This image continues to endure, albeit not as strongly as it was, but it is still effective.

To leave the shores of the Black continent and thrive in the West continues to be the height of ambition for many youths in Africa, even after contemporary political education has opened their eyes to the flaws beneath the oh-so-perfect veneer of life abroad.

The example of the USA and the West, as highlighted above, is very efficiently portrayed in Stephen Buoro’s The Five Sorrowful Mysteries of Andy Africa, where a young Nigerian boy has an unhealthy appreciation for all things Western at the expense of everything African.

Literature is one of the biggest drivers of popular culture, slugging it out with social media and motion pictures as the most significant contributors to national image in the world. The world reads predominantly about Black suffering. And, over time, we see this image become almost a stereotype. The trauma in African Literature is almost as iconic as the images of malnourished children with protruding bellies that Western media use to highlight themes of war, starvation, and disease in the Black Continent.

Both are grim realities. There’s no denying that Africa is beset with more problems than it can handle. However, in a world that is primarily made up of several shades of grey (albeit predominantly the darker hues), it could be argued that only a fraction of the African narrative is told in contemporary African Literature.

Literature, much like any form of art, is more than an expression of otherworldly inspiration: it is a business. The most popular works of contemporary African Literature today are predominantly trauma-themed. It is, after all, what sells.

The projection of despair, while of itself isn’t problematic, has unfortunately led to the commodification of trauma to incite pity and create a perpetual illusion of victimization. Now, to avoid being misunderstood, I shall break down the previous sentence.

Creatives have zero control over how their works are received. However, whether or not they’re aware of it, their works are laced with more than a dose of political agenda. The overwhelming motive for these politically-charged, hence trauma-inspiring works is borne out of necessity. After all, a writer can only channel their realities and experiences.

However, how audiences receive these works is a different matter entirely. In recent times, literature, and in fact, art, plays a massive role in cultural perception the world over. An over-commodification of traumatic themes in Africa means that Africans perpetually run the risk of being seen in a negative light everywhere in the world.

Unfortunately, it’s a matter of what sells. The world loves a good sob story. And the publishers are all too willing to oblige.

At this point, it becomes imperative to make two things clear.

One. The existing traumatic narratives are highly essential. They are also valid. It’s far from possible to pretend that things are fine when they are not. Messages have to be passed across. People need to be told the truth. Revolutions need to be fuelled. For a better world. For justice for the oppressed.

Two. The problem with the proliferation of books with such themes today is that they overwhelmingly dominate African publishing. Although there are no clear-cut statistics to support this, the eye test suggests that a significant number of African works feature these themes.

Fortunately, this trend is slowly changing. Literary fiction is slowly giving way to more genre-centric works in romance and speculative fiction, in particular. For instance, Nigerian publishers like Ouida and Masobe have created imprints like Oremaha, Tanja, and Phoenix to cater to more diverse themes and forms of literature, including fantasy, thriller, romance, comedy and children’s literature.

Just as well, the rights to more diverse works are being purchased, with Rogba Payne’s The Dance of the Shadows and M.H. Ayinde’s A Song of Legends Lost, a few in a long line of such books.

Many African Literature critics tend to shy away from the term “trauma porn” when describing certain equivalent works. The argument for this is that several other books in the genre don’t carry these attributes, which is true.

However, what is also unavoidably true is that the so-called “trauma porn” is now the face of African Literature globally. While this isn’t exactly the fault of writers or publishers, more can be done to show that African Literature isn’t primarily about depressing narratives.

There are beautiful romances, edged with the eccentric personalities that make Africans distinct worldwide. There are pulsating thrillers with unique dynamics that are rare to find in any other genre. And then, there are the fantasy stories.

Indeed, it can be argued that African myths and fantasy should be the hallmark of African Literature, and not the so-called “traum-porn.” It’s particularly noteworthy that some of the most commercially successful African-inspired narratives in recent years, such as Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone, draw inspiration from the myths and legends that are currently being undertold.

In fact, it is quite damning that Africans still have to rely on Western writers to write the stories that put them in the best socio-cultural light.

The biggest lesson here is that African Literature must, at last, wrest full control of the African narrative and dictate how it wants the rest of the world to perceive it.

The change is already underway. But the stereotype remains. Until the image is completely shed, African Literature will be synonymous with Africa’s bleakest realities, with no glimpse at its hidden riches.

The Tyrant Overlord. Fantasy buff and avid football fan.

Our list rounds up the top 30 cartoon characters that were villains, each one more wonderfully wicked than the last.

DC is great at making comics and animated movies, while the MCU has the upper hand in its cinematic aspects

Discover the best apps to read books for free in 2025. Access thousands of free e-books and audiobooks on your phone or tablet. ...

There are some outright funny cartoon characters who exist solely to crack you up, loud, hard, and with zero apology.

Things Fall Apart is for the colonizers as well as the colonized, helping to understand the role of colonialism in the realization...

While many of the Nollywood movies on our list are quite old, it’s a testament to the capabilities of the industry’s p...

While this isn’t an exhaustive list, it comprises some of the most popular mythical creatures from around the world.